“Why do you teach me ABC?” My precocious preschooler pointed to the virtual QWERTY keyboard on the tablet: “Why not ASD?”

As someone who studies the diffusion of innovations — how people learn and adopt new ideas and techniques — I wondered why indeed?

As someone who studies the diffusion of innovations — how people learn and adopt new ideas and techniques — I wondered why indeed?

And not just the ABC sequence. Many preschoolers already know words like Xbox, Yahoo and Zoom than xylophone, yacht, and zebra we have them rote. Wouldn’t teaching children the words that hold more meaning to them help keep pace with their experiences?

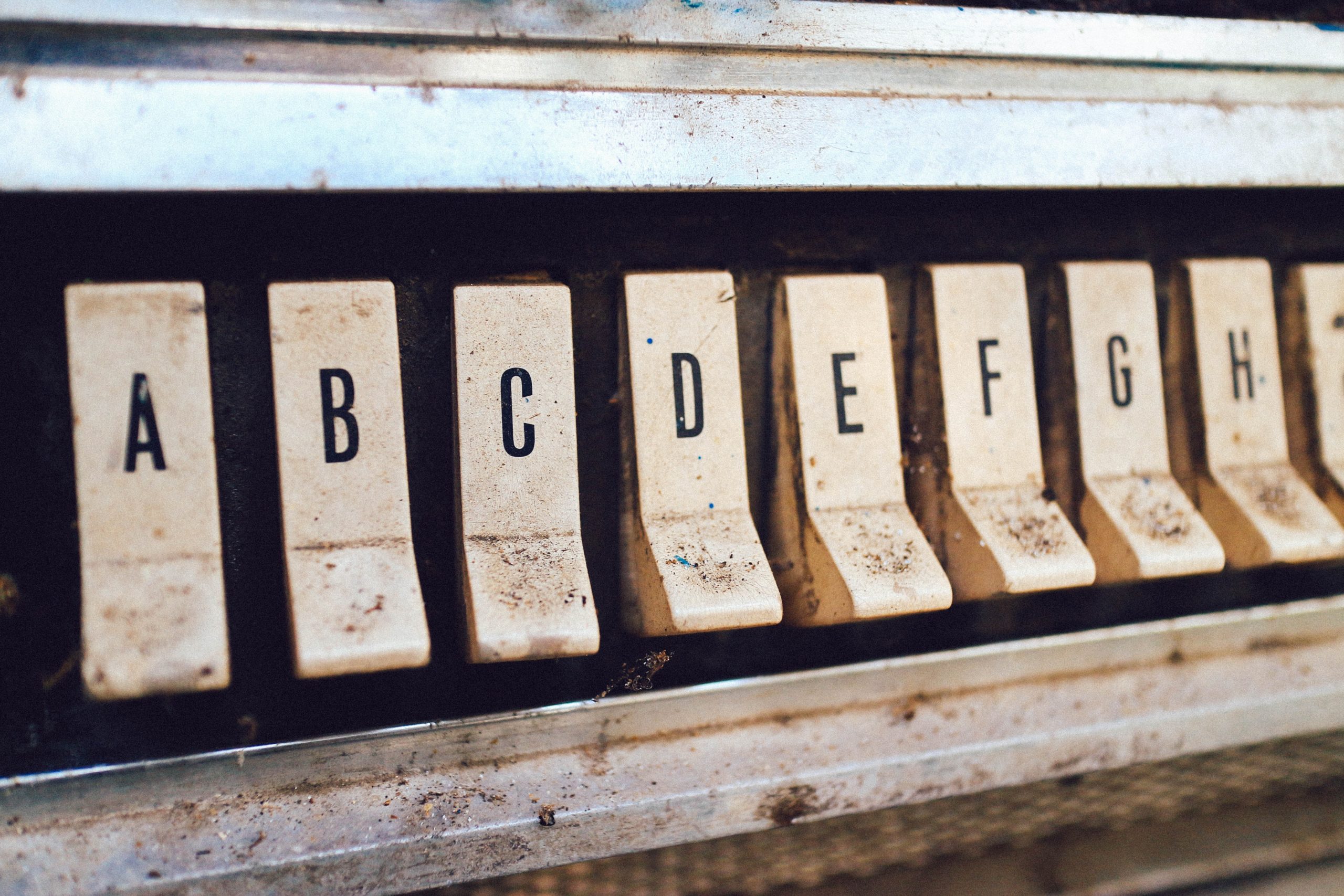

Of course, the QWERTY sequence is itself a product of modern technology. The layout was engineered by placing commonly typed characters farther apart to reduce the chance of font-keys in early manual typewriters from jamming when stuck together. Although completely unnecessary on today’s electronic keyboards, it has resisted all attempts over the past 50 years at improving its design. Teaching the sequence would, therefore, also be practical because it is the accepted norm, appearing in every input device from ATMs to airplane flight controllers.

Of course, the QWERTY sequence is itself a product of modern technology. The layout was engineered by placing commonly typed characters farther apart to reduce the chance of font-keys in early manual typewriters from jamming when stuck together. Although completely unnecessary on today’s electronic keyboards, it has resisted all attempts over the past 50 years at improving its design. Teaching the sequence would, therefore, also be practical because it is the accepted norm, appearing in every input device from ATMs to airplane flight controllers.

Many people, however, believe that the ABC sequence has remained somewhat fixed, while in actuality it has changed over time. Our 26 alphabets began sometime around the 15th century BCE in the Sinai as 22-characters, evolved with the Greeks into 25, and on through the Romans into Latin and the present set of 26. Z, which used to appear after F in Old Latin, was replaced with G, and transposed to its present placement. Here, too, technology and human development played a role. With migration and the expansion of people’s vocabulary, new inflections in speech arose, necessitation newer alphabets such as W. With the invention of writing tools and printing technologies came cursive scripts, lowercase letters, and the development of standardized font families. Thus, the ABC sequence is nothing more than a norm that people have overtime agreed upon — no different from QWERTY.

But there is an even stronger argument for teaching the newer sequence. Keyboards are tools for expression, no different from what pens are to writing or language is to literacy. And the sooner you are proficient with the tools, the better you can get at using it. Just as cultures with written languages, because of their ability to transmit knowledge with far greater accuracy, evolved to overtake cultures with spoken language, being adept as using the tools of expression sooner could lead to a higher quality of knowledge transmission. Thus, adapting to QWERTY sequence sooner would confer an evolutionary advantage for our children and likely even for all of us.

But that’s not all. Today, computing technology has also altered the way we write. Not only do we not use quills and fountain-pens, we rarely write by hand. And this has happened rather fast, even faster than the centuries it took for the evolution of alphabets and font families. Raised in the 1970s, I was taught to write in cursive, a skill which is seldom taught in US schools anymore. Instead, children in 3rd and 4th grade today “write” on computers where not just the writing style but also the process of writing is different.

Because you can only rewrite a document that many times, writing by hand, even on manual typewriters, required thinking before committing words on paper. Modern computers make writing innumerable drafts possible, which makes thinking as we write, without paying attention to style, spelling, or grammar in the initial drafts, possible. This has led to a change in how we write. As the renowned social psychologist Daryl Bem advocates in his oft-cited guide “…write the first draft as quickly as possible without agonizing over stylistic niceties.”

Newer word-processing apps have altered this process even further. While the ever-popular Microsoft Word allows for a sequential documentation of thoughts, newer apps like Textilus and Scrivener encourage non-sequential writing, allowing authors to tackle different sections, simultaneously, in draft form. Adding to this are advances in voice-to-text programs and machine-learning tools that can capture spoken words and suggest intelligent responses. Many of these, accessible at literally the flick of a wrist on many smartwatches and phones, have changed not just how we write but also our role as writers.

Finally, our idea of literacy itself is expanding. It’s more than just about knowing to write; it’s about being able to express information creatively. Children need to not only be adept at computing but also at finding information online, crafting persuasive content, and, while all of doing this, protecting their information trails. This requires two additional skills: digital literacy and cyber hygiene. The former equips them with information assessment skills, so they can find the right information and protect against disinformation. The latter instils digital safety skills, so they can’t be manipulated online and their information isn’t compromised. Both are essential for thriving in the virtual world where most of them spend their waking hours, even more so now since the pandemic.

Children are already familiar with an alphabet soup of online service before they step into a classroom. These skills are, thus, best introduced in their formative learning, not in middle school and college where they are presently taught. This will ensure that the next generation is equipped to transmit information with even greater accuracy and creativity all the more sooner — an advantage that will accrue to them and to our society as a whole. The first step towards this involves mastering the QWERTY keyboard.

- A version of this post appeared here: https://medium.com/@avishy001/why-do-we-still-teach-our-children-abc-7f8cde35ec39

- **Photo source