Photo by Mariia Shalabaieva on Unsplash

Phishing emails are everywhere. You are far more likely to receive phishing and spam messages than legitimate ones. Over the years, I have written about this problem using a term I still find useful: email hygiene. By that, I did not just mean inbox cleanup or filtering rules, but the cognitive-behavioral conditions under which email is trusted, read, and acted upon.

Years of security awareness training have taught users to be vigilant and skeptical. People are trained to scan emails for cues of danger, to hesitate, to doubt intent. That vigilance has helped reduce some attacks, but it has also produced an unintended effect.

Security awareness has trained people to distrust email, including legitimate internal communications.

This is not accidental. Repeated exposure to phishing simulations, warnings, and post-failure messaging conditions people to associate email with risk. Suspicion becomes reflexive. Negative framing of mistakes, public reminders of failure, and constant emphasis on threat prime users to fear getting email wrong. Over time, email itself becomes a stressor rather than a channel for communication.

As a result, success in email communication is no longer about delivery alone. It is about whether the message is received, trusted, and internalized. The goal is not simply to land in the inbox, but to get through.

This is where email hygiene needs to be rethought.

Photo by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

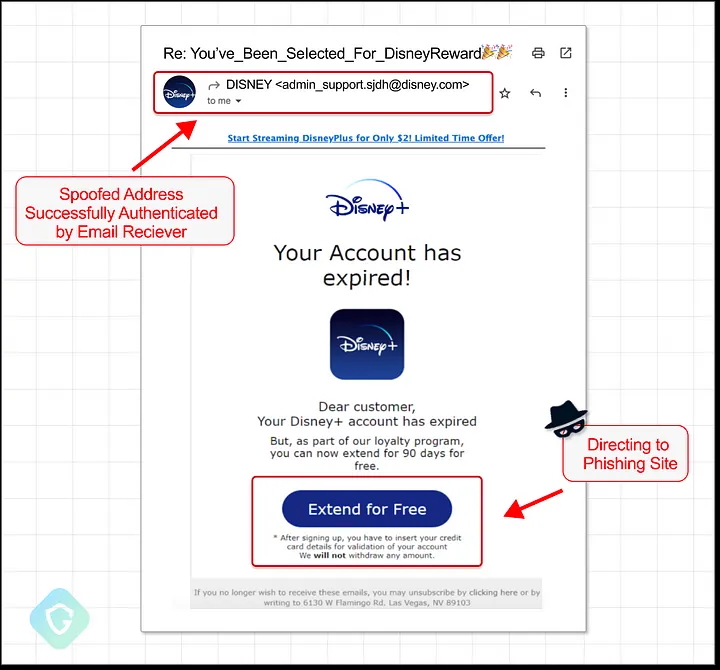

Email hygiene is often framed narrowly as avoiding phishing. Do not click suspicious links. Block malicious senders. Improve filtering. Add banners. But email hygiene is not just about avoiding phishing. It is also about avoiding looking like phishing. Internal communications that trigger the same cues users have been trained to fear are likely to be ignored, delayed, or questioned, regardless of their legitimacy.

Much of the guidance in this space misses this point. It focuses on user behavior, on technical controls, or on generic communication advice that is disconnected from how security training has reshaped user perception. What is often overlooked is that internal communicators themselves can unintentionally reproduce the very signals people have been trained to distrust.

The first point of failure is often the sender and subject line. Emails from generic inboxes that users do not recognize are immediately suspect, especially in large organizations. Messages are more likely to be trusted when they come from a real, credible individual. When a generic inbox must be used, familiarity matters. Prior exposure through other channels helps establish legitimacy before the email ever arrives.

Subject lines require particular care. Users have learned to associate urgency, warnings, rewards, threats, and artificial deadlines with phishing. Even small cues, such as typos or misleading reply markers, can undermine trust. Organizations benefit from consistent conventions that allow users to recognize legitimate internal messages without having to guess.

The body of the email matters just as much. Messages should feel human and intentional, not templated or rushed. Errors in opening or closing lines are especially damaging, as they signal inattention or automation. Before asking for action, emails should first establish credibility and context. Only then should they clearly state what is being asked, why it matters, and what happens if no action is taken.

Verification also plays an important role. Emails should be signed by a real person, even when sent from shared inboxes. Providing non-email contact paths allows recipients to verify authenticity without replying to the message itself. Logos and branding can help, but they are no longer sufficient on their own. These cues are frequently reused by attackers and even in internal phishing simulations, which further trains users to distrust them. Cross-posting important messages on internal sites gives users a way to confirm legitimacy outside the email channel.

Finally, when messages are broadcast widely, it helps to test them with a small audience first. Even limited pre-testing can surface unintended phishing cues before they reach thousands of inboxes.

Email is a flexible medium, and there is real craft involved in using it well. No set of rules can guarantee success. But good email hygiene reduces confusion, avoids triggering conditioned suspicion, and increases the likelihood that legitimate internal communications are not just delivered, but believed and acted upon.